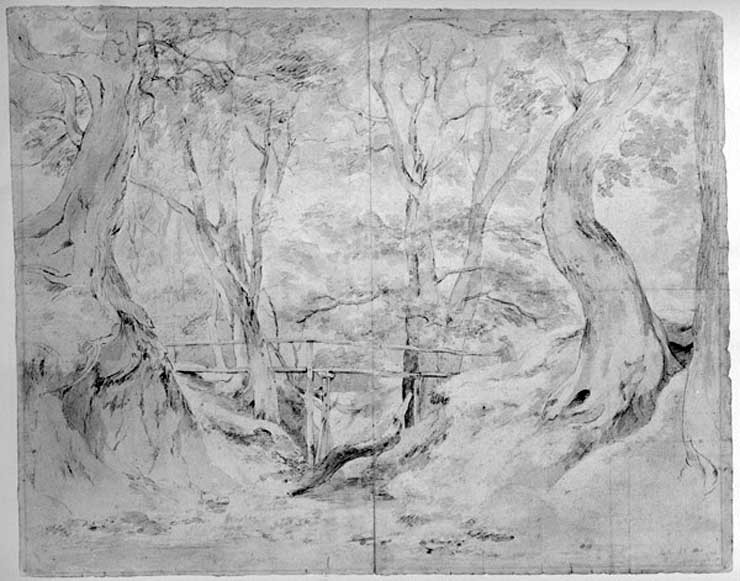

As a young student, John Constable spent the summer of 1800 sketching in the park of Helmingham in Suffolk, England. In the 1820s he returned to his pen and ink drawing and worked it into full-size oil paintings. Dell at Helmingham Park, at one time owned by the art collector John G. Johnson, was made in 1825-26 for James Pulham, a friend of Constable who lived near the park. He again returned to the subject in 1830, one of the paintings he did is in the Nelson Atkins Museum in Kansas City and I did a copy in undergraduate school at KCAI. This is probably the drawing he worked from.

Constable’s Dell at Helmingham Park

This is the painting – it’s pretty large, 44-5/8″ by 51-1/2″. Looking at a small reproduction It’s hard to feel the same the sense of space you get when you stand in front of the painting – it really draws you into the space of the dell and you feel as if you were surrounded by the woods. As your eye moves over the scene you look up into the trees on the right and down into the creek where the cow stands. If you hold your face really close to your screen you might get a hint of how it feels to stand in front of the painting.

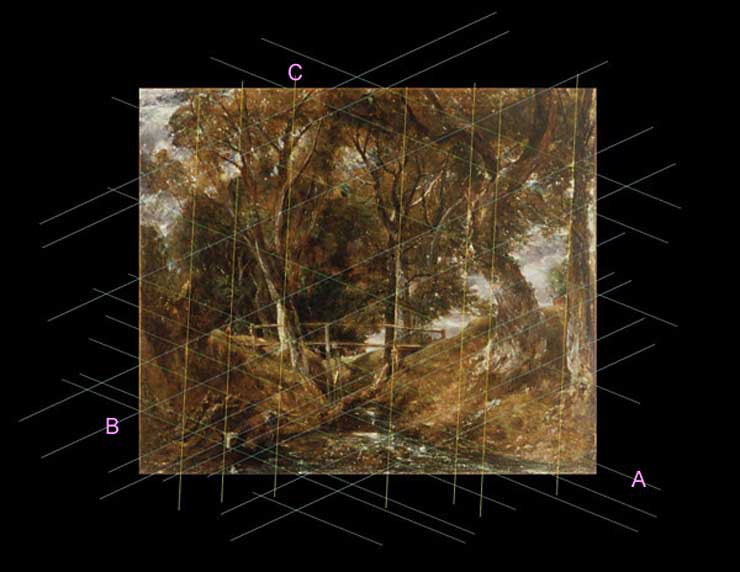

Diagonal Structure

This and the next image illustrates a set of three diagonals that seem to me important to the pictures structure. I find it useful to limit the number of diagonal directions, in this case to three. The painting is enormously complex and pulling out specific structures is helpful. Notice how the diagonals that follow A and B repeat the sloping contour of the hills on either side of the creek. Diagonal C follows the bridge posts. You can see how these lines build a spatial geometry for the lower third of the painting. In the next one, two of the diagonals remain the same and the one closest to vertical changes.

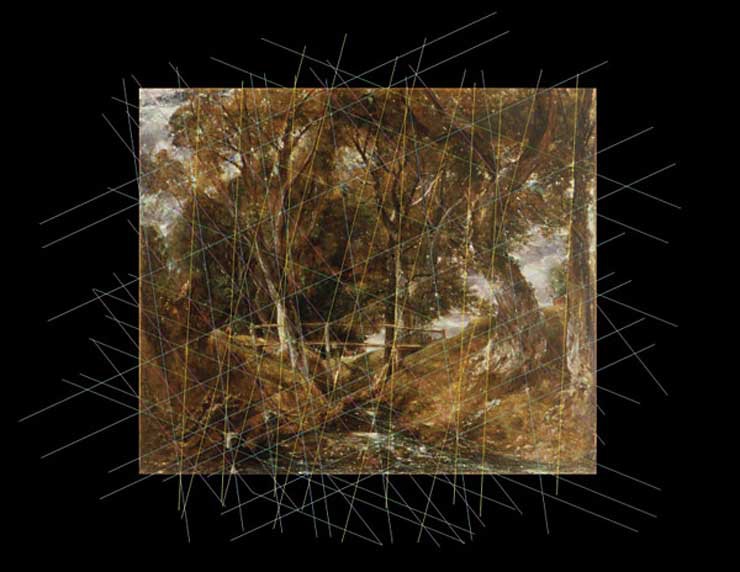

Now our diagonal C follows the tree trunks and you can see, especially on the right, builds a geometry that opens up the top of the painting, also the space above the bridge. Simplifying the geometry makes it clearer but the next one is more complete.

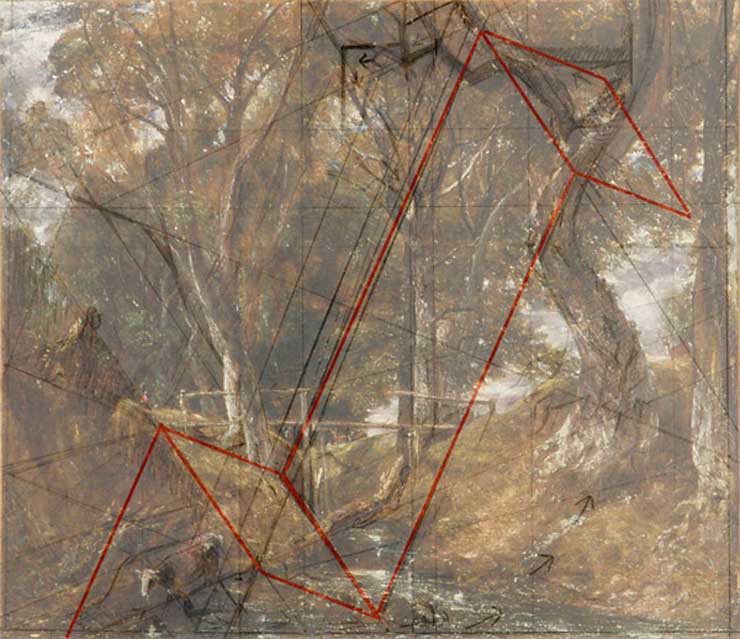

Here is the painting with most of the diagonals that seem relevant to me. It seems pretty complex but on the other hand because there are so many possibilities most any structure can be built into the painting and all will be beautifully inter-related and harmonic. Next we’ll look at how to build some planes into the structure.

Here I tried to clarify some of the planes that Constable suggested in the painting. The connections and suggestions are picked up by our “constructing visual brain” to create space – just as we create space in the real world. I enjoy the sensation of “I know it’s flat but it doesn’t feel that way”. I also started thinking about eye paths and how that works and tried to work on my awareness of how I was reading the painting, that’s next.

But first here is a really simple representation of two planes in the Constable. We are looking left and right but also up or down depending on which is closer to you, points A and B, or point C. If you look through the right plane point B seems closer than C, if you look down into the water point C seems closer.

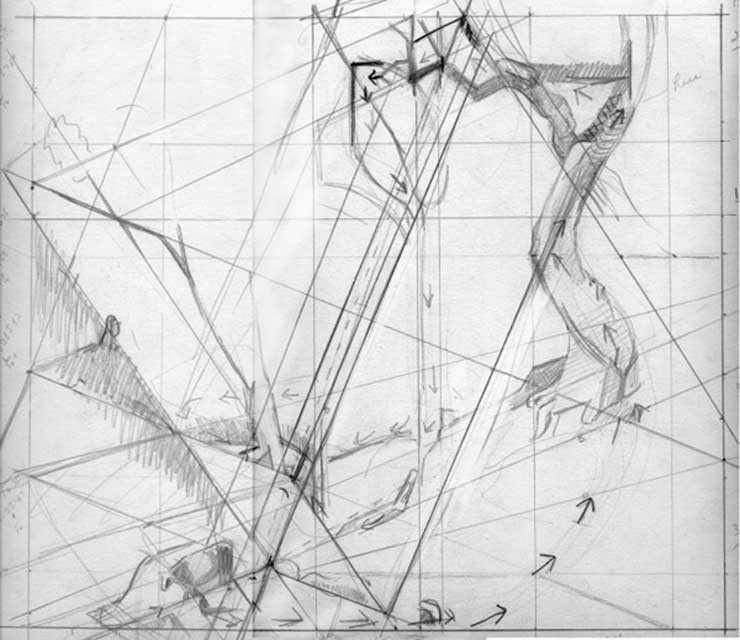

This is a drawing that developed out of an attempt to understand how reversals (shifting readings like the necker cube), planes, and the eye path of the viewer work together in a painting. One thing that seems clear to me is that tension, created when you brain tries to resolve a visual conflict, creates a visual path space that moves from one reading to another. This one is about the tension between the trees above and the cow and creek below. Notice how the twisting branches work to create planes, The next one overlays the drawing onto the painting.

The overlay of the drawing emphasizes what I think happens in your peripheral vision when you look closely at the twisty tree branches at the top right. You might try it yourself by looking at the original image above and really look at those branches, See if you can be aware of, without looking directly, the lower left quarter of the picture. I feel the hill at point A pulling forward instead of behind point B.This opens up a big spatial form that really separates the twisty tree from those behind. And the cow walks down and into the space created. When you look directly into the lower left point B comes forward and a the space between the edge of the left bank and the trees near the bridge opens up. The pushing and pulling of the spatial elements directs you eye through the picture. The next is one possible reading.

You can see how the plane that describes the left bank of the hill flips and how it could relate to it’s adjacent planes. There are lots of possibilities here, the point is that the geometry is a flexible structure that holds opposing tensions. You could find smaller planes and movements as well. The big structure is handy because it serves to tie the painting all together.

Our Visual Intelligence at Work

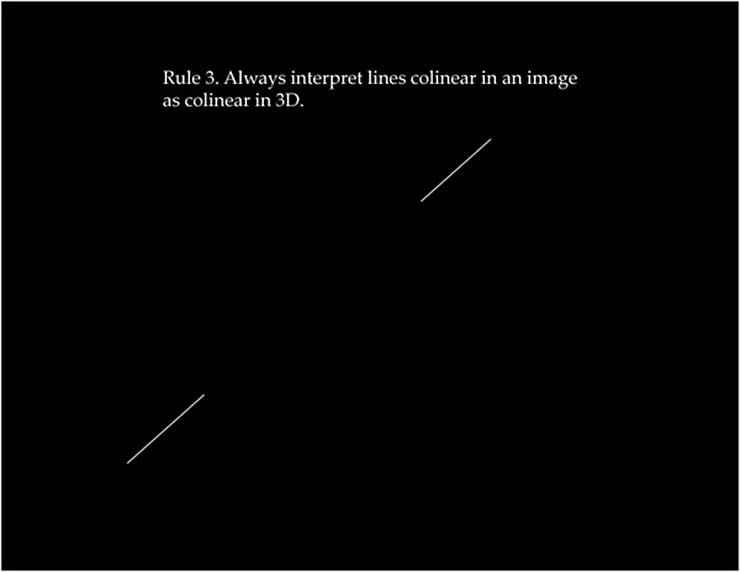

This is rule three from Donald Hoffman’s book Visual Intelligence. When we see two lines like this our brains read them as if they were parts of the same line in 2D and in 3D. So even if the full line does not exist we read it as connected. The next illustration fills it in.

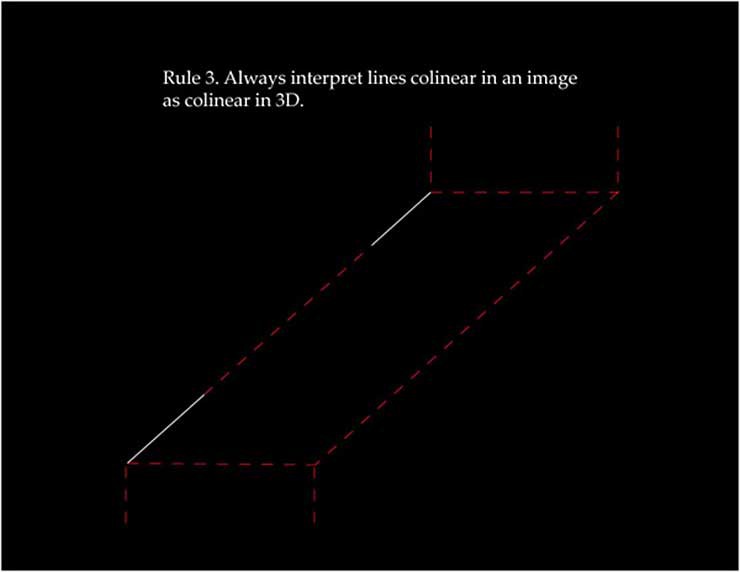

Here it is with our favorite reversing planes. A painter can take two pieces of a line shove them forward and back in space and you will read them as one connected line, lines indicate planes and create space.

Here are the col-linear lines on top of the Constable painting. I hope you can feel the spatial tension and how a plane is created. We love seeing connections and our visual brain is busy constructing all day long.

Leave a Reply